The impact of the climate crisis on venues and athletes

This page reviews the many ways in which climate change is already taking its toll on global sport, and the scale of the risks and difficulties ahead.

It looks at six current dangers and future threats:

- Winter sports face climatological and economic demise as the geography, volumes, and frequencies of snow fall shrinks.

- Players and the public alike are threatened by more heatwaves and the range of heat illnesses; more and more events are being rescheduled or cancelled as a consequence.

- Drought is a practical threat and a huge economic cost for turf sports like cricket and football.

- Air pollution, already bad in many cities, is made considerably worse by global heating and has negative effects on both the quality of sporting performance and the health of athletes and spectators.

- Extreme weather events like hurricanes, typhoons, storms, and floods are becoming more frequent and more powerful causing considerable disruption to sporting schedules and sometimes massive damage to sporting facilities.

- Sea level rises and flooding together pose considerable threats to many urban coastal stadiums, grassroots playing fields, beach sports and surfing, and coastal golf links.

The impacts of climate change will, of course, not be uniform, but one almost universal consequence of the changes is that average temperatures will rise everywhere. In mountainous regions that are home to most winter sports, it will mean less snow, falling less often, and melting more quickly. Changes in precipitation, without which there is no snow, are also diminishing snowfall in many places. Obviously, winter sports are directly affected by these problems.

Winter Olympics

In January before Vancouver 2010, local temperatures were the warmest on record at 4.6 degrees Celsius above normal, and temperatures during February when the games were staged were 3.4 degrees Celsius above normal.

Snow cover was OK at the high mountain venues at Whistler, but at the lower altitude of the Cyprus Mountains venues, the organisers coyly wrote that “the warmest weather on record ... challenged our ability to prepare fields of play for athletes.” In fact, a huge 24/7 operation to create and move artificial snow was required.

Many competitors at Sochi 2014 complained about the lack of snow, and that the artificial slow, wet, and heavy snow was difficult to manoeuvre on.

These poor course conditions meant that most medal winners came from amongst the first ten athletes to start in each competition, as they had the huge advantage of racing on drier snow that was quickly degraded for those that followed them.

Compared to the 2010 Games, there was a five per cent drop in athletes actually finishing their event in alpine skiing, freestyle skiing and snowboarding. There was also a nine per cent increase in competitor injuries.

The Sochi Paralympics saw a sixfold increase in injury rates compared to Vancouver.

Pyeongchang 2018 had no problem with snow, but it is worth noting that, like all the other recent Winter Games, these Olympics required the destruction of significant mountain forest, and the reassignment of protected land and national parks to permit development.

Beijing 2022 suffered, above all, from the prolonged drought that the host mountains had endured. A massive operation was required to make enough artificial snow, and then only enough to place a ribbon across parched brown slopes.

Future Winter Olympics

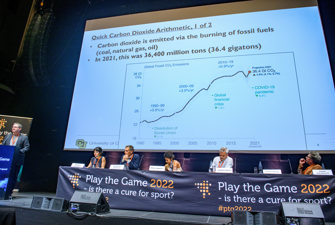

According to predictions made by researchers at the University of Waterloo, Beijing is just one of many former hosts that are unlikely, for climatological reasons, to be able to do so again. Of 19 prior locations, only ten were thought to still be reliable winter sports hosts in 2050, and just six in 2080.

In more recent research, based on more up-to-date climate models, the Waterloo researchers estimate that under a high emissions scenario, only Sapporo will still be a reliable Winter Olympics host by 2080.

The winter sports industry

The global winter sports tourist industry is equally imperilled. Due to the lack of snow and the poor quality of what snow there is, the season is starting later and finishing earlier. The number of good skiing days is diminishing. See for example studies of Norway, Sweden, Austria, the US and Canada.

Already, more than 90 per cent of all ski resorts worldwide are using artificial snow, but this requires not only significant capital investment but also large amounts of water and energy. Water, in particular, can be difficult or very expensive to access in mountainous regions suffering from droughts.

Even where snowmaking is technically feasible, these costs are likely to put many lower-altitude resorts out of business.

Key readings

K. Pierre-Louis and K. Popovich, N. “Of 21 Winter Olympic Cities, Many May Soon Be Too Warm to Host the Games” New York Times Jan 11 2018 (subscription)

Sport Ecology Group (2022) Slippery Slopes: How Climate Change is Affecting the Winter Olympics

Scott et. al (2022) Climate change and the future of the Olympic Winter Games: athlete and coach perspectives

The physiology of overheating is complex, but once you start hitting 33 to 35 degrees Celsius it’s all bad news, for spectators, officials and above all athletes.

- Increasing temperatures negatively affect memory, eye-hand coordination, and concentration, all of which means poorer sporting performance.

- Sunburn is already a considerable problem in some sports and is likely to get worse and the risk of skin cancer correspondingly increases.

- Physiologically, high temperatures raise levels of sweating and heart rates and raise the risk of dehydration, muscle cramps, and cardio-vascular problems.

- These symptoms can combine to produce heat exhaustion and, most seriously of all, the multi-organ failure of heat stroke.

All of this is made worse in high humidity. Sports organisations now calculate safe temperature thresholds by reference to both heat and humidity, which when combined produces what is referred to as a wet bulb temperature.

There are already a variety of mitigation strategies in sport to cope with this threat. They include:

- more cooling and hydration breaks

- events scheduled at cooler times of the day or year

- heat acclimatisation strategies for athletes

- alterations in game/race strategy

- new sports clothing.

At the same time, more events are just being cancelled, and in other case more athletes put at risk.

Key reading

BASIS (2020) Rings of Fire: How Heat Could Impact the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

One inevitable consequence of more hot weather is less rain, and in many parts of the world that means more droughts. This is a problem for any lawn-based sport that requires lots of water to prepare playing fields.

- The 2018 prolonged drought in Cape Town in South Africa saw water use at both professional and amateur sports grounds severely restricted. The visiting Indian cricket team was told to shower for no more than 90 seconds while club and school cricket was cancelled halfway through the season across the whole Western Cape. Reports of pitches cracking were widespread.

- In 2016, the Mumbai high court forbade the Maharashtra Cricket Association in India from receiving water for its matches in Pune from depleted reservoirs, forcing the games to be relocated.

Droughts also affect rates of flow in rivers. Lower water flow will have an impact on multiple riverine sports (canoeing for example) both in terms of sporting performance and the cleanliness of the water.

Air pollution comes in many forms and has many sources. Particulates, heavy metals, ozone, and acids make up a poisonous cocktail, and athletes are breathing in more of this than most.

During a peak air pollution episode in Delhi in 2017, cricketers playing in the India v Sri Lanka game were vomiting on the pitch, and it was necessary to have repeated breaks in play and to install oxygen cylinders in their dressing rooms.

Climate change is making air pollution, already awful in most of the world’s metropolitan areas, much worse.

Many habitats overwhelmed by longer periods of drought, hotter and longer summers, and large-scale and inappropriate human developments, are increasingly at risk of massive wildfires. The scale of the fires in Australia in 2020, for example, saw tennis and cricket events overwhelmed by smoke.

Increasing temperatures also lead to higher levels of ozone at ground level which has a serious impact on pulmonary functioning. Air pollution researchers have found that high exposures diminish the athletic ability of football players, and the quality of baseball officials’ judgements.

Key reading

M. Tainio et al. (2021): Air pollution, physical activity and health: A mapping review of the evidence, Environment International, vol. 147

The last thirty years have seen a steady increase in the number of hurricanes, typhoons, and storms, and an increase in their average severity. Many parts of the world are experiencing greater levels of precipitation, and new geographical and seasonal patterns of rainfall. These are already having significant impacts on sport.

- Caribbean hurricanes have smashed cricket facilities in Anguilla and Dominica. Powerful Pacific typhoons arriving on Japan’s eastern coastline led to games being cancelled at the 2019 Rugby World Cup, and schedules for surfing and sailing to be rearranged at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

- A more incremental but equally problematic change can be seen in English cricket where, for example, 27 per cent of home One Day Internationals since 2000 have been played with reduced overs because of rain disruptions, and the number of rain-affected matches has doubled since 2011. Five per cent of matches have been abandoned altogether over the last decade with considerable economic consequences.

- Amateur and recreational sports are also affected by the new weather. In England in 2014, the average grassroots pitch lost five weeks per season to bad weather, and a third of these pitches lost between two and three months in a season.

Beach and coastal sports

Beaches are amongst our most important natural sports fields. Sea level rises and the inevitable land erosion that goes with them threaten professional and recreational sports alike.

- The islands and archipelagos of the south Pacific are amongst the landscapes most threatened by sea level rises, and their rich rugby cultures, nurtured on their beaches, are equally imperilled.

- California’s beaches and their surfing culture are also looking insecure. One recent study predicted that 18 per cent of the state’s most popular beaches will be lost by 2050, that another 16 per cent will be in decline, and that two-thirds of all beaches in the southern half of California will be gone by the of the century.

- The R&A reports that one in six of the coastal British Open championship courses, including St Andrews, Troon and Carnoustie, are unlikely to last out the century.

- Scotland’s Montrose golf course, one of the five oldest in the world, has been forced to sacrifice its third tee, to provide sufficient rock defences for the even more threatened first and second holes. It expects to lose more. The Royal North Devon golf club, entirely flooded by Storm Deirdre in 2018, saw the eighth hole disappear into the shingle beach.

Stadiums at risk

In 2020, the report ‘Playing Against the Clock’ used mapping technology and mainstream climate change and sea level models to look at the risks of flooding facing major stadiums in North America and Western Europe. It reported that:

- Bordeaux’s Matmut Atlantiq stadium will, by 2050, be completely flooded on an annual basis, while Werder Bremen’s Weserstadion can expect annual partial floods.

- In the United States the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars and their TIAA Bank Field, as well as the NBA’s Miami Heat and their American Airlines Arena, can expect annual partial floods.

- The New York Giants and Jet’s MetLife Stadium and the New York Mets’ Citi Arena will, by 2050, be completely flooded every year.

- In Canada, the Edmonton Oilers’ Rogers Place and Toronto FC’s BMO Field will be partly flooded on an annual basis.

- Of the then 92 league teams in England, 23, almost one in four, can expect partial or total annual flooding of their stadiums by 2050. Those under threat in the current Premier League are Southampton’s St Marys, Chelsea’s Stamford Bridge and West Ham’s Olympic Stadium.

- In the Netherlands, in 2050, the stadiums of Alkmaar Den Haag, Groningen, Heerenveen and Utrecht can look forward to total annual flooding with partial floods for Ajax and Feyenoord.

Thick smoke from raging wildfires across Australia is seen across Melbourne ahead of the 2020 Australian Open. Photo: Darrian Traynor / Getty Images

Examples by year of climate impacts on global sport

2014

- The Australian Tennis Open was played in the middle of a harsh heat wave that saw four consecutive days of temperatures above 41°C. Frank Dancevic actually began hallucinating on court before vomiting and departing, one of a record nine players that retired during the first round of play. During the whole tournament over 1,000 fans were treated for heat exhaustion.

2015

- In the northwest of England, the huge rainfall that came with Storm Desmond saw Carlisle United’s Brunton Park flooded, and the club was forced out of the stadium for seven weeks at considerable financial cost.

2017

- Anguilla’s main cricket stadium, James Ronald Webster Park was seriously damaged by Hurricane Irma requiring a total rebuild.

- Windsor Park cricket stadium in Dominica was devastated by the category 5 Hurricane Maria.

2018

- At the 2018 US Tennis Open temperatures on court peaked at 49 degreesCelsius. Officials mandated the first use of the tournament’s extreme heat policy, allowing more and longer breaks during matches. Nonetheless, five players retired from matches for heat-related reasons.

- In Indian cricket, thirteen Indian Premier League games were moved from Maharashtra due to the worst drought for 100 years.

2019

- The mid-summer heat wave in the Eastern USA saw the cancellation of New York City Triathlon.

- The Tokyo 2020 Olympic organisers finally bowed to climate realities and rescheduled the marathon and long distance walking events 1000 km north to Sapporo to escape Tokyo's now humid and dangerously hot summers.

- Typhoon Hagabis came ashore in Japan with such torrential rain and winds that three games at the Rugby World Cup were cancelled.

2020

- Critical drought conditions threatened the cancellation of the South Africa vs India test match in Cape Town.

- A combination of record temperatures and raging wildfires across Australia saw dangerously polluted conditions at the Australian Tennis Open in Melbourne and Big Bash cricket matches in Sydney.

- Storm Ciara was sufficiently powerful to force the cancellation, in England, of one Premier League game, and six Women’s Super League matches and widespread postponements in Dutch football and the top two levels of Belgian football.

2021

- A typhoon that made land fall during the Tokyo Olympics forced a major rescheduling of rowing and surfing events. The heatwave in Tokyo city saw a rescheduling of tennis matches.

- Storm Eunice swept across Northern Europe precipitating huge flooding across the Low Countries and Western Germany. High winds tore part of the roof of ABO Den Haag’s Stadium. Belgium's F1 circuit Spa-Francorchamps was flooded. The Koningsee, the world's first artificial sliding run, was smashed into pieces. The German Olympic Committee reported 100 million Euros worth of damage to sports facilities.

2022

- Record floods in KwaZulu Natal, on South Africa’s Indian Ocean coast, destroyed many of the region’s golf courses.

- Fierce summer heatwaves saw the New York triathlon shortened and the Boston triathlon cancelled.

Winter 2022/23

- One of the warmest European winters on record saw the postponement or cancellation of many events on the world skiing circuit, as well as economic disaster for the tourism and leisure industries in France, Italy, and Switzerland.