Sustainable innovations in sport

Many of the climate actions that sports organisations are taking, like switching to renewable energy and investing in building insulation, are the same actions that any organisation needs to take. However, in a number of areas sports organisations are responding to the unique challenges and opportunities arising in sports.

The examples range from rethinking sports stadiums over redesigning sports competitions to developing new business models, materials and products in the sports goods industry.

On this page, you will find case examples of sustainable innovations from

- Seattle's Climate Pledge Arena

- SailGP's Impact League

- Extreme E's spectator-free events

- a number of companies in the sports goods industry

Seattle's Climate Pledge Arena has the ambition to set a new sustainability bar for the sports and events industry. Photo: Steph Chambers / Getty Images

Making stadiums sustainable: Seattle’s Climate Pledge Arena

At the heart of most professional and commercial sports is the sports stadium. At their largest and most expensive, these are now billion-dollar pieces of infrastructure of considerable architectural and social complexity. Making them and the events they stage sustainable is, perhaps, the single most important task facing the industry, but it is an enormously complex one.

Seattle’s Climate Pledge Arena is the first major new stadium to put all of these issues right at the heart of its conception and construction and is an operational innovator in the industry.

The Climate Pledge Arena is the latest incarnation of what began as the Washington State Pavilion at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair and served as the city’s main indoor sports arena for half a century. In 2016, the city of Seattle initiated a further redevelopment and was joined by NHL franchise the Seattle Kraken, developers Oak View Group and Amazon, who bought the naming rights and called the stadium the Climate Pledge Arena with the ambition to “set a new sustainability bar for the sports and events industry.”

Construction

Rather than demolishing and rebuilding the area from scratch the developers chose to retain the iconic, swooping roof of the original stadium and saved a considerable amount of materials and carbon emissions in the process.

More carbon emissions were prevented by reusing 30,000 square feet of glass from the original stadium and reinstalling it in the new arena’s facade.

This plan required the roof to be raised up on a massive steel scaffold while the old stadium beneath it was demolished, and a deep bowl was dug out beneath it to house the new enlarged arena and its facilities.

Some of the earth was reused locally and all of the carbon emissions associated with it counted towards the stadium's overall footprint. The old gas heating systems were removed, and the new arena was designed with a 100 per cent electric energy supply.

Certification

The arena’s carbon footprint and eventual aspiration to be carbon zero is being monitored and certified by the Seattle-based International Living Futures Institute, whose Zero Carbon Certification programme demands higher sustainability stands than LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), which is the current leading certification programme for green buildings.

The ice rink

The arena’s ice is made from rainwater harvested from the arena’s roof. It is then frozen using natural rather than high-carbon refrigerants, and polished and maintained by a fleet of electric ice resurfacing machines.

Energy

A small amount of the arena’s energy is generated on-site from solar panels on the roof, but the vast majority is purchased offsite. The strict certification rules that the arena has chosen mean that it cannot just buy in renewable energy that is already being generated but must contribute to creating new and expanded sources of clean energy.

Initially, the arena is purchasing and then retiring renewable energy credits from a local wind farm to compensate for power that it is taking from the existing grid, and then it plans to buy all of its power from new local solar farms.

Transport

All tickets for events at the arena come with free public transport use. The arena is well served by bus services, light rail, and monorail. Cycle valet parking is also available.

Food and drink

The arena has committed to providing food and beverages where 75 per cent have been sourced locally.

It has introduced reusable, recyclable, and compostable packaging and cutlery and is aiming to have removed all single-use plastics by 2024.

Climate education

The main lobby of the building houses a 200-foot living plant wall and within it an LED wall that informs visitors about the arena’s carbon-zero ambitions and keeps track of its current carbon emissions.

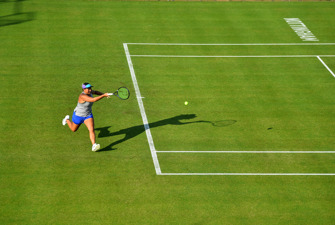

World Sailing launched SailGP as a global competitions promising to be a carbon-positive sporting spectacle. Photo: Ezra Shaw / Getty Images

Redesigning sports competitions

Rethinking key features of sport has also been a source of innovation in designing more sustainable formats for sports competitions. Read the cases from SailGP and Extreme E.

SailGP was launched in 2020 and is one of World Sailing’s global competitions. It features nine teams on a global circuit of races, and under the slogan Race for the Future, it promises to be a carbon-positive sporting spectacle. Its ambitious decarbonisation programme includes all boats and technical equipment, support services, host and spectators villages, and broadcasting.

Host cities must now sign SailGP’s Climate Action Charter and commit to two projects, one of which must involve clean energy, and the other should focus on ’blue carbon’ – projects that maintain and restore “critical carbon-sequestering shoreline ecosystems” like salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrass beds which, per square metre, absorb and store considerably more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere than most forests.

It is also looking to be a significant voice for climate education, mobilising events and athletes to draw attention to oceanic plastic pollution, and the threat of sea level rises and coastal flooding.

One of its key innovations is the Impact League. Alongside points scored for racing, each team is scored on ten environmental and social categories: Sustainability strategy; tech and innovation; clean energy; merchandise; waste and single-use plastic; travel and accommodation; food; using your voice; diversity, equality and inclusion; and NGO collaboration.

At the end of the season, the winner of the Impact League takes the podium alongside the winner of the regular league and receives a cash prize for their nominated NGO partner. In its inaugural season, the Impact League was won by the New Zealand SailGP team, and their USD 100,000 prize went to NGO Live Ocean which will fund research into kelp forests to explore their potential to sequester carbon emissions.

Having significantly reduced its scope 1 and 2 missions, SailGP is now tackling scope 3 emissions and has recently signed a new deal with its logistics supplier that is carbon neutral.

Extreme E, launched in 2021, has nine teams racing off-road in electric SUVs in locations that are threatened by climate change including deserts, rainforests, and artic landscapes, drawing attention to the threats we face.

Given the remoteness and fragility of these kinds of locations, there are no spectators, in person at Extreme E events. This makes its carbon emissions considerably smaller than any other motorsport, indeed any other comparable sporting event.

As an alternative, fans can use the app GridPlay which allows them to follow the race, interact with teams and drivers, and vote for their favourites who are rewarded with pole positions.

Extreme E has also established a legacy programme, working with NGOs on environmental projects in the location it has staged races.

Extreme E, launched in 2021, has nine teams racing off-road in electric SUVs in locations that are threatened by climate change including deserts, rainforests, and artic landscapes, drawing attention to the threats we face. Photo: WPA Pool / Getty Images

Making the sports goods industry sustainable

One of the biggest contributions that sports could make to climate action is making the global sportswear and equipment industries sustainable.

Sports organisations and athletes have significant potential leverage with sportswear corporations who eagerly sponsor them, building their brands and sales in the process.

In return, global sport should increasingly demand and expect their sponsors and suppliers, at the minimum, to use only recycled plastic or plant-based materials to create entirely recyclable goods and to use their reach and influence to support climate action.

Below, you can find a number of recent initiatives in this field that include new business models and the development of new materials and products.

Most companies, whatever their environmental policies, are primarily driven by the pursuit of shareholder value and profit. This means that they are under relentless structural pressure to produce and sell more. Outdoor clothing company Patagonia’s recent transformation into a climate-oriented social business offers an alternative.

In 2022, Patagonia’s founder, Yvon Chouinard, announced that he would transfer his shares in the company, worth around three billion euros, to a charitable foundation. Patagonia itself would be transformed into a non-profit organisation. Profits generated by the company that are not reinvested are to be transferred to a charitable foundation that will support climate action.

In the global north people are buying on average around 60 items of clothing a year, and more than 40 per cent of them will sit unused in drawers and wardrobes. Sportswear is no different and a great deal of sports equipment sits either unused or infrequently used in sheds and garages.

Renting clothing and equipment is one simple way of massively reducing the sector’s carbon emissions. Already widespread in parts of the cycling and winter sports industry many companies are expanding the range and availability of these kinds of services.

German company Globetrotter, for example, rents tents, backpacks and bags, water sports equipment, bikes, and outdoor equipment for children. In France, Decathlon has explored renting outdoor equipment and clothing via its own brand. German ski brand Schöffel started renting skiwear in Austria and Switzerland where deliveries are made directly to customers’ accommodations.

In grassroots sport, kit and equipment libraries have also begun to emerge. As the single most effective way of reducing consumption and emissions, as well as making sport more accessible, supporting these kinds of initiatives should be a priority for the sports industry.

While many sportswear companies are trying to use more recycled plastic in their clothing, and have also tried to make those products themselves recyclable, they have hit a series of technical problems.

Adidas’ Terrex jacket is a good example of some of the kinds of innovation that the industry needs to pursue. Many garments are hard to recycle because the different kinds of artificial fibre and plastic used in their production must all be separated.

Consequently, this jacket is made of just one material – polyester – and thus is entirely made from recycled materials and is itself easy to recycle. However, this required a design that dispensed with zips and buttons that can’t be made of polyester.

Winqs’ Zerofly running shoes contain a range of small innovations that make them made almost entirely from plant-based or recycled materials. These include:

- an outsole made of hybrid rubber itself made from rubber waste

- a midsole made in part from castor seeds

- an inner lining that uses Lyocell which is made from wood pulp

- an upper covered in a thin layer of 100 per cent recycled polyester

- packaging that uses only recycled paper and plastic-free cardboard boxes

- repair service to extend the life of all shoes

- a commitment to take back all shoes and take care of responsible disposal.

While much of the focus in the industry has been on clothing, sports equipment is also a major producer of carbon emissions. Plastics and materials like carbon fibre rely on a lot of fossil fuels.

One interesting set of innovations has been used by Finnish winter sports company Loska and textile manufacturer Spinnova to create plant-based skies.

These skies are made of wood, but with a core made from fibres spun from natural cellulose obtained from recycled wood and textiles. The manufacturers claim that their performance is as good as any conventional competitor.

Adidas’ latest iteration of its Terrex jacket has incorporated Spinnova materials into its design.