Sports’ response to the climate crisis

The last decade, and especially the last five years, have seen a serious shift in sports’ engagement with the climate crisis. This section maps and begins to evaluate the sector’s response.

On this page, you can find:

- practical examples of how the most advanced international sports federations have attempted to deliver on their commitments.

- examples of best practices from national sports federations and commercial leagues.

- examples of a flowering of sports climate action from below, driven by new campaigning NGOs, athlete activism, and fan engagement.

- a mapping of the environmental response of the world’s football clubs.

Read more about the different global frameworks for adressing climate change in sport

UEFA released its new environmental policy in 2022, as part of a wider programme of social responsibility commitments. Photo: Anadolu Agency / Getty Images

Case studies: International federations

Below you can see practical examples of how UEFA, World Athletics and World Sailing – some of the most advanced international sports federations – have attempted to deliver on the commitments they have signed up to under UNSCAF or Race for Zero.

UEFA released its new environmental policy in 2022, as part of a wider programme of social responsibility commitments. The policy is still in development but breaks new ground in its commitment to a circular economy model. Some of the most innovative policies are being developed alongside the DFB in Germany for the staging of the Euro 2024.

Goals:

- To reduce European football’s carbon footprint and be a credible reference partner for organisations working on climate protection, with a target of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 50 per cent by 2030, and achieving net zero carbon by 2040 within UEFA, across UEFA events, and collaboratively across European football.

- Embed the circular economy – the '4R approach’ – built around reducing, reusing, recycling, and recovering – into European football which means the “optimisation of the consumption and life cycle of products, most notably food, packaging, and branded items throughout UEFA operations and events."

- Set a new benchmark for zero-impact sporting events by developing and rolling out UEFA’s own sustainable event management system.

- Raise the bar for European football infrastructure by setting criteria and sharing best practices for a new generation of sustainable football venues.

Support for federation members

- Not much support. UEFA’s focus is overwhelmingly on its own organisational units’ events rather than its members’ national-level activities.

Offsets:

- UEFA experimented at the 2016 European Football Championships with a campaign and an app that would allow fans to offset their own carbon emissions when attending the tournament, but the take-up was lamentably low.

- For the Euro 2022, UEFA decided to absorb the entire costs of offsetting the aviation emissions.

- For the Euro 2024, the report by the Oko Institut recommends investing in greenhouse gas reductions within German football as the most efficient and reliable way of achieving ‘climate responsibility’ rather than ‘climate neutrality’.

Spectator transport:

- Plans for Euro 2024 include signed, safe routes known as ‘fan miles’ that will allow fans to reach the stadiums easily on foot or by eco-friendly public transport.

- Bike-sharing stations will be set up for staff at the stadiums.

- The tournament’s Combi-Ticket Plus is designed to make low-carbon public transport cheaper and more appealing to fans, not only for travel to Germany but also to cover the long distances between venues.

Sponsors:

- Plans to actively involve sponsors in developing sustainability solutions.

In 2019 World Athletics unveiled its environmental strategy. It is one of the first really serious attempts to go carbon neutral amongst sports federations.

Goals:

- Carbon neutrality by 2030 across World Athletics operations and events based on an annual 10 per cent reduction in emissions from a 2019 baseline.

- All events sanctioned by WA are required to commit to carbon neutrality targets.

Policy on member federations:

- World Athletics plans to encourage and support member federations to join the UN’s Sport for Climate Action Framework.

- Provides sustainability workshops to member federations.

Offsets:

- The policy is to “identify credible means to offset unavoidable emissions”.

Spectator transport:

- World Athletics does not, as yet, commit to dealing with the emissions generated by spectators, but is planning to add emissions from athlete travel to the WA carbon footprint.

Sponsors:

- Planning for all corporate partners to be engaged and active around an aspect of sustainability by 2030.

World Sailing with its Sustainability Report 2030, is one of the few Olympic sports federations that currently commits to a carbon reduction target with a plan to cut emissions at events by 50 per cent by 2024.

Goals:

- World Sailing aims to be the first international federation to achieve and maintain a third-party-certified ISO 20121 management system.

- Cut emissions by 50 per cent by 2024.

- Close alignment of policy to the full range of the United Nations’ SDGs, with a special emphasis on oceanic pollution, plastics, and biodiversity.

Support for national federations:

- Created a sustainability charter that all members have to sign as a condition of membership.

- World Sailing plans to encourage national sailing events to achieve the highest level of sustainability standards set by 2030.

- Sustainability training to be included in its Emerging Nations Programme.

- Include modules on sustainability in all World Sailing training/coaching programmes by 2020.

Technical standards:

- World Sailing plans to develop technical standards by 2030 to reduce the environmental impact of the sailing industry focusing on the end-of-life of composites and engine and energy technology.

- The strategy introduces higher environmental standards for boats, for example, so to participate in the 2028 Olympic Games, 90 per cent of a boat must be recyclable, and waste from the production process must be halved compared to 2018.

- It also requires a 50 per cent reduction in boat building waste (by weight) across all World Sailing classes by 2030.

- All race yachts under World Sailing classes and ratings will not be solely reliant on fossil fuels to produce power on board, or for auxiliary drive by 2030.

- Single-use plastics are to be abolished at international and national sailing events by 2030.

Offsets:

- No policy

Spectator Travel:

- No policy

Sponsors:

- No policy

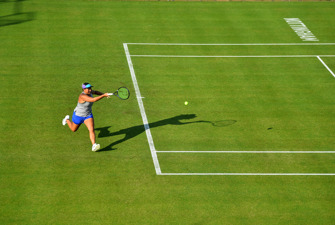

The English Lawn Tennis Association is signed up to Race to Zero as an organisation, as an event/competition owner and operator, and as a national governing body. Photo: Mike Hewitt / Getty Images

Case studies: National federations and leagues

Below you can find case examples of best practices from the English tennis association LTA (a national sports federation) and the Bundesliga (a commercial league).

LTA is signed up to Race to Zero as an organisation, as an event/competition owner and operator, and as a national governing body.

Goals:

- to achieve net zero carbon emissions from LTA operations and major events by 2030

- to support the wider tennis community in reducing carbon emissions

- for tennis in Britain to have a net positive impact on biodiversity

- for policy to be aligned with the full range of UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Policy for federation members:

- to embed sustainability into the local governance framework of English tennis

- to ensure that all national, county, and island associations have a sustainability plan by 2026

- to offer sustainability training to all LTA-accredited coaches by 2026

- ensure that all LTA facility investment has a sustainability element by 2026.

Offsets:

- No policy as yet.

Spectator transport:

- Promote travel by public transport for major tournaments

- Engage with international tennis tours on reducing international travel impacts

- Sponsors

- Seek out sustainability-focused commercial partners by 2026.

Timetable:

- Ensure that all electricity for LTA facilities is sourced from renewable supplies by the end of 2023

- Reduce organisational carbon emissions by 25 per cent by 2026 and 75 per cent by 2030

- Reduce operational carbon emissions from events by 75 per cent by 2030.

In 2020, proposals were put forward by a network of German fan groups arguing that the Bundesliga’s annual financial audit of clubs should be accompanied by an audit of their environmental performance, with the ultimate sanction of refusing a playing license to those clubs making insufficient progress. The Bundesliga has taken up this idea and the audits will begin in 2023.

Goals:

- Clubs must demonstrate a sustainability strategy and an environmental strategy for licensing for the 2023/24 season and appoint a sustainability officer.

- The environmental strategy must analyse the environmental impact and emissions of the club locations and set targets and interim goals.

- The clubs must collect a range of other data, for example on their energy and water consumption as well as their wastewater production.

- Clubs are required to look at ways to reduce waste.

Support for league members:

- A data platform for the clubs is planned to help them to collect and evaluate information.

- Guidelines and templates for analyses will also be supplied, as will further training opportunities for club employees.

Offsets:

- No policy.

Spectator travel:

- Clubs will also have to conduct a mobility and traffic analysis and develop an environmentally friendly mobility concept on this basis.

Sponsorship:

- No policy.

Surfers Against Sewage was founded in 1990 by Cornish surfers to campaign against sewage discharges into the sea. Over the last thirty years, they have expanded their work to campaign on climate, plastics, sewage, and water quality across the UK. Photo: Nur Photo / Getty Images

Climate action from below: NGOs and campaigns

Over the last five years a whole range of organisations which campaign internationally and nationally on climate and environmental issues in sport have emerged. Some focus on sport in general, while others focus on a specific sport.

All of these organisations are engaged in lobbying the official sports federations, professional clubs, and franchises. Some have been set up to work specifically with athletes, developing and nurturing them as climate activists, others have sought to engage fans and supporters in a climate dialogue. A few also focus on grassroots and amateur sports, but generally, there is a significant gap in this field.

As with the formal response to the climate crisis, these organisations are overwhelmingly in the global north, and especially North America, Australasia, and Northern Europe. Where they have emerged in the global south, it is in the form of youth-related environment and development projects.

This list is not comprehensive, as new initiatives are emerging all the time, but it gives a good sense of the scope, geography, and forms of sport and environment NGOs.

At a global level, the Sport Positive Summit organises an annual conference amongst the more than 300 signatories of the UN Sports for Climate Action Framework. Sport Positive also organises the research and publication of Sustainability Leagues for the national football leagues Premier League, Ligue I, and the Bundesliga.

Sport and Environmental Education is an EU-funded programme that looks to use outdoor activities, including sport, as a tool for wider environmental education.

Sport and Sustainability International works across all sports on environmental issues as an advocate and think tank. Two of its main programmes are a football-specific campaign on climate, football4climate, and its research programme at the Sustainable Sports Lab.

BASIS, the British Association for Sustainability in Sport, is now ten years old and has played a vital role in igniting the environmental conversation in UK sport. Alongside advocacy, network, and research it provides consultancy services to the industry.

At a national level multi-sports campaigns have recently emerged in continental Europe, the largest so far being Sports For Future in Germany which has been joined by Sports for future Switzerland.

Two organisations founded by athletes complete the current picture. We Play Green, backed by Norwegian football player Morten Thorsby and Formula 1 driver Sebastian Vettel, mixes advocacy and grant-giving, while the Big Plastic Pledge, established by the British Olympic rower Heather Mills, has been campaigning and working to remove plastic from all levels of sport.

Surfers Against Sewage was founded in 1990 by Cornish surfers to campaign against sewage discharges into the sea, and they are pioneers in this space. Over the last thirty years, they have expanded their work to campaign on climate, plastics, sewage, and water quality across the UK.

Founded in 2007 by professional snowboarder Jeremy Jones, Protect Our Winters gathers together winter sports athletes to protect cold environments and campaign for climate action. It has commissioned research on the future of winter sports and lobbied the US government and has received considerable support from winter sports goods manufacturers. Initially based in North America, there are now branches in Japan, Australasia, and across Europe.

Founded in 2020, Football for Future works on a variety of fronts to make English football environmentally sustainable. Projects include climate education at football clubs, working with professional footballers as climate ambassadors, and providing environmental consultancy to football clubs.

They have been joined in English football by the Football Supporters Association - England who have voted to campaign on climate issues and partnered with Pledgeball to engage fans on the topic. In France, Football Ecologie France works with football clubs at every level of the game, providing environmental audits and consultancy, as well as projects to engage fans on climate action.

English journalist Tanya Aldred, who has written extensively on cricket and the climate crisis, has created the website The Next Test which has gathered together a great range of information on the subject and campaigns on social media for change in the game.

They have been joined in this space by Cricket for Climate, launched on the back of an open letter to Australian cricket authorities calling for radical action on climate. It is fronted by Australia’s cricket captain Pat Cummings but joined by many cosignatories from the men’s and women’s games.

So far only small initiatives have emerged in cycling and running. In Norway, Green Cycling is campaigning on climate issues, engaging cyclists, and looking at ways of making cycling more sustainable.

Runners Against Rubbish, an English organisation, is as the name suggests, campaigning for runners not to litter either as individuals or during organised races.

Recent years have seen a major step up in the level of athlete activism. Empowered by social media and acquiring a degree of financial and personal autonomy that earlier generations of athletes did not possess, they have been finding their voices: from Colin Kapernick’s decision to take the knee, to the impact of Black Lives Matter on English football, to Marcus Rashford’s work on food poverty in Britain. The growth of climate activism amongst athletes is part of this wider trend.

A range of organisations have emerged to support, train, and amplify athletes who want to speak up on climate issues: In North America, Ecoathletes has been the leading NGO, in the UK the same work is done by Champions for Earth, and in New Zealand, Lite Foot occupies this space.

In Australia, there are currently two organisations that cover all sports, Players for the Planet and Frontrunners, while Australian rules football players have created AFL Players for Climate Action.

Finally, Common Goal, which has worked with football players and coaches, has recently added issues of climate to their agenda. Common Goal’s approach is to ask players and coaches to donate one per cent of their income to football and development projects and to support them as advocates for social change.

The Rapid Transition Alliance, a UK think tank and activist network, has launched a campaign to get fossil fuel companies out of sport and published a report on the subject in 2021, ’Why sports should drop advertising and sponsorship from high-carbon polluters’. In 2022, they have been calling out the world of sport with their ‘Bad Sport and Greenwash Awards’ campaign.

A more focused NGO that grew out of a campaign amongst Liverpool fans around the fossil fuel investments of the club’s sponsor Standard Chartered, has now gone national as Fossil Free Football.

Football has proved to be the main sport, so far, in which fan engagement on environmental issues has taken off.

In England, two rapidly growing fan engagement NGOs have emerged in football. Pledgeball, which works at all levels of the game to encourage fans and players to make environmental pledges that score points in online competitions with other clubs.

Planet League takes a very similar approach, again focusing on football, while in Australia the Sustainable Sports Programme has tried to use this model across all sports.

Football has also been used as a tool in educating youth and supporting environmental regeneration programmes, especially in the global south. Examples include Global United FC, Green Kenya, Seacology and Spirit of Football.

Key readings

J.Amman (2021) 1:0 for the environment: Engaging football fans on tackling climate change

M. Campelli (2021): Could mobilising football fans be a key climate action strategy? Sustainability Report

J.M. Casper, M.E. Pfahl and B.P. McCullough (2017): Is going green worth it? Assessing fan engagement and perceptions of athletic department environmental efforts Journal of Applied Sport Management, 9

C. Poole (2021): How to reach & engage sports fans on sustainability and climate change in a credible and meaningful way, Sports Positive Summit

Arsenal has focused its efforts on renewable energy. They have installed solar panels on the roof of the Emirates Stadium and have also installed large lithium batteries to store electrical charge, which provides power for the stadium for much of the week. Photo: Rob Newell - CameraSport / Getty Images

Climate action in football clubs and leagues

Below, you can find a mapping of the environmental response of the world’s football clubs. As the world’s most popular sport, football, is the biggest prize for climate action in sport, while the depth of the relationship between clubs and fans offers a very promising arena for climate advocacy.

Latin American football has, so far, not taken up the sustainability challenge, except for the pioneering Argentina club, Estudiantes de La Plata, which has taken the construction of a new stadium as the opportunity to embed sustainability at the heart of the club’s operations.

The Premier League is a recent signatory to UNSCAF, but has yet to develop a comprehensive policy or insist on minimum environmental standards from its members.

There are currently four clubs in the Premier league who are signatories to the UNSCAF: Liverpool, Southampton, Tottenham Hotspurs and Arsenal.

The overall environmental performance of the Premier League clubs can be seen in the Sports Positive sustainability league.

The EFL (English Football League) is responsible for the three lower divisions in England, and has launched its own sustainability model – EFL Green clubs. Though membership remains voluntary the vast majority of its 72 clubs have signed up.

Clubs:

- Forest Green Rovers, now in league one of the third level of English professional football, has been the pioneer of sustainability in English football. Owned by Dale Vince, chair of the green energy company Ecotricity, they have combined success on the field (rising up from non-league football through successive promotions) with significant investments in renewable energy, organic turf culture, and vegan food. They currently have planning permission to build a zero carbon new stadium, the first to be made of wood since the 19th century.

- Arsenal has, so far, focused its efforts on renewable energy. They have installed solar panels on the roof of the Emirates Stadium and have also installed large lithium batteries to store electrical charge which provides power for the stadium for much of the week. For the rest of their energy needs, they have signed up with an exclusively renewable energy supplier.

- Liverpool has branded its sustainability policy as The Red Way, and interestingly has applied its principles to the planned expansion of the Anfield Road

- Southampton has branded its sustainability policy as The Halo Effect. Their 2021 sustainability report features new kits partly made from recycled ocean plastic, and the phase-out of single-use plastic cups.

- Tottenham Hotspurs made issues of sustainability central to the design and construction of its new stadium and is perhaps the leading club in the EPL on these issues. It was the first club in the Premier League to stage what it referred to as a zero-carbon game. They have also created an organic vegetable garden at the training ground which supplies their canteen and have mobilised many of their players, like Eric Dier, as environmental ambassadors.

Given the strength of the environmental movement, it is no surprise that Germany is a leader in football and sustainability. It has been a pioneer in offering free or discounted public transport to match ticket holders for example.

The overall environmental performance and ranking of Bundesliga clubs can be seen in the Sports Positive League.

While many clubs have good policies and programmes, a few stand out.

- Wolfsburg, although owned by Volkswagen, has a particularly strong and well-documented sustainability policy.

- TSG Hoffenheim: Details of Hoffenheim’s strategy are discussed in this podcast from the Sustainability Report with emphasis on the sustainable sportswear brand that the club has created in Africa. The club has also invested in tree planting programmes in Uganda and stages a kick-for-climate football tournament in Namibia.

- Werder Bremen has recently signed up for the UN’s Race to Zero programme. The club has tried to reduce car use by getting a ban on parking around the stadium on match days and investing in a boat taxi service to the ground. It also encourages its staff to support the climate strikes.

Bohemians FC, a fan owned team from Dublin, is the leading Irish club on sustainability issues. They are the first to appoint a climate justice officer and in 2021 they hosted an Environmental Justice Film Festival.

Italian football has been slower to take up the sustainability agenda, and its football federation has, so far, been silent on the issue. However, two of its clubs are making progress:

- Juventus has been on this journey for almost a decade as its detailed annual reports make clear.

- Newcomer Udinese has been innovating, particularly with new recyclable kits and green messaging on their shirts.

Hibernian FC, based in Edinburgh, was the first Scottish team to sign up for the UN Sports for Climate Action Framework. One interesting example of its work has been its use of bamboo shinguards cutting down on plastic consumption. The club has recently been joined in this work by Aberdeen FC.

Real Betis from Sevilla is the pioneer in Spanish football. Its extensive work on energy, water, and transport has been used to create an open platform for other clubs to follow called Forever Green under the slogan No Planet, No Football. It has recently partnered with La Liga which is encouraging all of its member clubs to join the programme.

MLS, like other major American sports leagues, has signed up to the UN Sport for Climate Action Framework and has developed its own sustainability guidelines.

- First out of the blocks on the topic, preceding MLS by some years were LA Galaxy who in 2016 launched their Protect the Pitch.

- Portland Timbers and Thorns have put sustainability alongside equity, diversity and community at the heart of their operations and values. Recent work includes a switch to one hundred per cent renewable energy supplies.

- One interesting newcomer to US soccer and sustainability is Vermont Green. The club was founded in 2021 and played its first season in the fourth level of US soccer in 2022 with an explicit and radical environmental agenda that emphasises racial and climate justice. The founders can be heard discussing their vision and plans for the club in this podcast from the Sustainability Report.