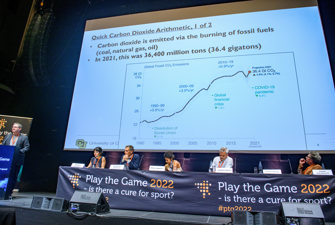

Global frameworks for addressing climate change

Three global frameworks have been set up to guide sports towards lower carbon emissions. So far, only a small part of the sports sector has signed up for them.

This page looks at the newly developed global frameworks for climate action in sport: ISO20121, a global standard for managing environmentally sustainable sports events, the UN’s sport for climate action framework (UNSCAF), and its more challenging Race for Zero programme.

While UNSCAF with over three hundred signatories including the majority of international sports federations marks a major advance, it is important to note what a small fraction of the sports world it actually covers, and how few of the signatories have begun to seriously implement the commitments they have signed up to. Nonetheless, amongst the best of the signatories, there are real signs of what could be possible.

Global frameworks for addressing climate change

There are, at present, three global frameworks which are guiding sports’ carbon-zero ambitions:

ISO 20121 is a management system created as part of the London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics that is designed to help organisations staging events to be socially responsible and environmentally sustainable.

UNSCAF (UN Sport for Climate Action Framework) was created in 2016 by UNFCCC and some of the leading world sports organisations, including the IOC, FIFA, and UEFA.

Race to Zero is a global UN-backed campaign to achieve net zero carbon emissions ‘by 2050 at the latest’. Its signatories include businesses, cities, and regions.

Note, there are other ISO standards that some sports organisations draw upon, like UEFA’s use of ISO 14001 which specifies the requirements for an environmental management system that an organisation can use to enhance its environmental performance; and the EU Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) which is a premium management instrument developed by the European Commission to help companies and other organisations to evaluate, report, and improve their environmental performance.

See also the recent EU Council initiative ‘Green and sustainable new deal for sport’.

Increasingly, national climate plans and directives from national ministries of sport are impacting sports organisations’ climate action. In France for example, more than 100 sports organisations signed up to a national charter pledging major changes in sports consumption of transport, food, and energy.

The three frameworks can be distinguished by:

- the main environmental goals and objectives of the frameworks

- the criteria for joining the programme and commitments required

- the support offered to organisations joining a programme, and forms of audit on their progress

- their policy on spectator travel

- their policy on sponsorship and climate

- their policy on carbon offsetting.

|

|

ISO20121 |

UNSCAF |

Race to Zero |

|

Goals |

The standard requires that an organisation has in place a transparent process through which it systematically evaluates the issues relevant to its operations and sets its own objectives and targets for improvement. |

Signatories are now requested to commit to a range of climate actions:

|

A review group examines all organisations' applications. Signatories must commit to

|

|

Commitments on joining |

None |

The organisation’s CEO must:

|

The organisation’s CEO must:

|

|

Support and audit |

Support: |

Audit: |

Audit: |

|

Spectator travel |

|

|

|

|

Sponsorship |

|

Calls for signatories to engage and work with stakeholders on climate action, but there is no prescriptive policy |

No policy |

|

Offsets |

As yet no position on offsetting, but a review is promised |

No position on offsetting |

Permits offsets provided it entails ‘purchase of valid offset credits’, certified to the highest global standard. |

Events that have used ISO 20121 include the London 2012 Olympics and Paralympics, COP 21 in Paris in 2016, horse racing at Goodwood in the South of England, Formula E, and the 2016 Rio Olympics.

It has not, however, established itself as the environmental/sustainability certification system for events. Some sports organisations consider it too cumbersome and too process-driven and given its lack of target setting, too timid for the rapid decarbonisation efforts required.

UNSCAF has now over three hundred signatories, including most of the world sports federations like FIFA, the UCI, and World Athletics. Cricket, however, is conspicuous by its absence. After that things get more eclectic. There is a scattering of stardust from the NHL and the NBA, the New York Yankees and the New York Mets, four teams for the English Premier League, and a dozen other football clubs. Some of the global commercial tours are also present – like Formula 1, Formula E and Golf Saudi – alongside the German Ski Instructors Association, Bowls Australia, and Sky Sports.

The Global South, while not totally absent ( Kenya Athletics for example), is massively underrepresented. Impressive as the numbers may seem, it is a very, very long way short of where the sports industry needs to be.

Just under one hundred of the signatories have also signed up to the more stringent Sports for Climate Action.

Key reading

E. Hawkins (2022) Sport and climate change – what is the guidance?