Beijing 2022: To the moon and back

ANALYSIS: What does the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics and space politics have to do with each other? Quite a lot and it demonstrates China’s ability to mix sport and politics in their national self-promotion, writes senior analyst Stanis Elsborg.

At every closing ceremony of the Olympics, it is a tradition that the coming host has an artistic show called the handover ceremony that often gives a glimpse of the cultural and political agendas the new host wants to promote. Spectators of the Chinese handover ceremony at the end of the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, were treated to a visual feast created by Zhang Yimou, the renowned Chinese film director, who – according to an official handout for the tv-commentators called the media guide – wanted to "use modern methods and thinking to display a rich mixture of Chinese cultural elements with winter sports and project an image of China in a new era".

This era is a high-tech era where China wants to place itself at the top of the podium.

The whole visual identity of the handover ceremony looked like a starry sky as seen from outer space. 24 roller skaters, who all came from Beijing Sport University, looked like astronauts flying around in space while they left behind curving trails with the assistance of high technology.

These trails later turned into a vibrant Chinese Long, also known as a dragon. Afterwards, the gliding trajectories evolved into a Chinese Phoenix, and according to the media guide "the Long and Phoenix are, in Chinese culture, symbols of good fortune, representing the Chinese people's good wishes and blessings for the Winter Olympics." This mix of both high technology and Chinese culture was a key theme throughout the ceremony.

Along with the 24 ice skaters, there were also 24 television screens attached to automatic guided vehicles that presented an audio and visual celebration that combined technology and Chinese culture into one.

From the Beijing 2022 handover ceremony. On the tv screen, you can see a Chinese spacecraft. Photo: Getty Images/Maddie Meyer

From the Beijing 2022 handover ceremony. On the tv screen, you can see a Chinese spacecraft. Photo: Getty Images/Maddie Meyer

The television screens especially highlighted China’s high-tech inventions such as the high-speed rail of China, modern Chinese cities, The National Stadium, also known as the Bird’s Nest, high-speed railway bridges, and the ‘Heavenly Eye’ – a 500-meter telescope inaugurated in Guizhou in 2017 which will be of great importance for China’s science and innovation-driven development.

Also on the screens were China’s first independently manufactured large passenger jet, C919, and the Tianzhou 1, China's cargo spacecraft, which in 2017 succeeded a flight mission, setting the stage for "a space station era" and China's manned spaceflight programme.

This focus on high technology and space technology has since the handover ceremony in 2018 continued in the narrative of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics and the new China exemplified in the Olympic mascot of the 2022 Beijing Games: The panda Bing Dwen Dwen, who is dressed as an astronaut.

Space politics in sport?

The 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics will not be the first time that sport and space politics are mixed. During the Cold War, the two superpowers – the United States and the USSR – fought a symbolic war in both sport and space. It was "war minus the shooting" as the English writer George Orwell would say. In both fields, it was a matter of showing which social system was the most superior.

In fact, the Soviet triumphs in outer space gave the Americans so great a shock that it spurred them to develop the Apollo programme, which in 1968 eventually led the US to put a man on the moon.

But the two spheres were also mixed, especially during the 1980 Olympics in Moscow and the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. During the opening ceremony of the 1980 Olympics two cosmonauts communicated directly to the audience and viewers in a direct connection from cosmos. And four years later at the opening ceremony of the 1984 Olympics, rocket-man William Suitor was wearing an astronaut suit while he flew across the Olympic Stadium using a jet pack.

At the 2014 Sochi Olympics, the Russian president Vladimir Putin also used the event to illustrate his space ambitions. Space policy was the main theme at the opening ceremony highlighting the Soviet contributions to space technology. But it was the Olympic torch’s trip to the International Space Station that really demonstrated the Russian state’s desire to become an international superpower in space.

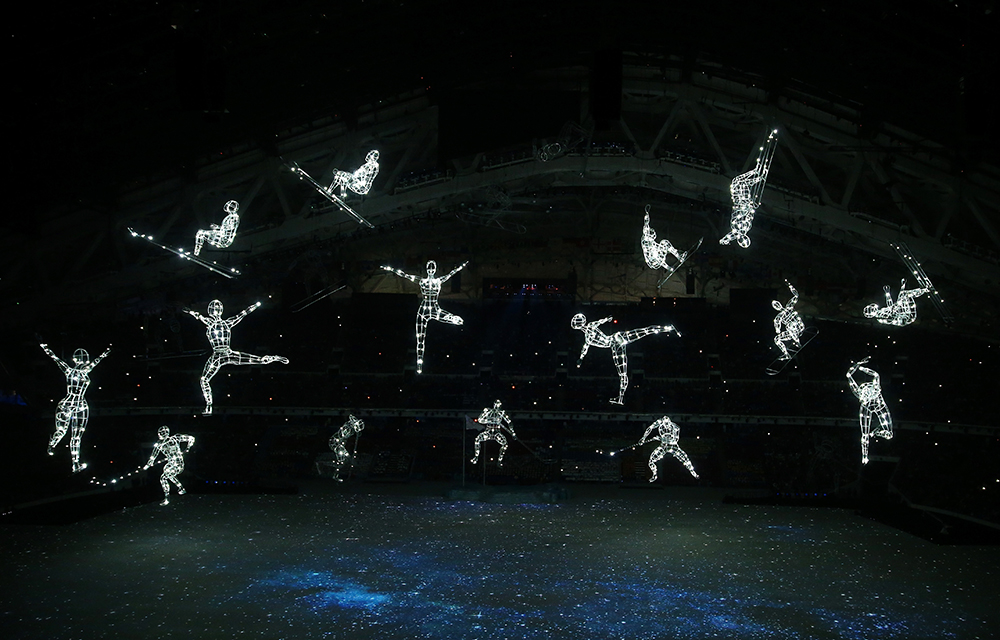

Elite sport and space politics were core themes at the opening ceremony of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. A symbol of Putin’s desire to once again place Russia as both a superpower in sport and space. Photo: Getty Images/Bruce Bennett

Elite sport and space politics were core themes at the opening ceremony of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. A symbol of Putin’s desire to once again place Russia as both a superpower in sport and space. Photo: Getty Images/Bruce Bennett

A new space race?

The US and Russia still invest a lot in becoming the superpower in space, but at the beginning of the new millennium, China has emerged as a new challenger in the political battlefield of sport and space. Just as the Americans in 1957 became obsessed with the idea that the road to world domination went through space, China, especially in the last three decades, has had a similar revelation.

Aerospace engineering and space technology is a significant part of China’s very ambitious plan "Made in China 2025" (MIC 2025), that was launched in 2015 by Prime Minister Li Keqiang. The state-led industrial policy seeks to secure China’s position as a global powerhouse in high-tech industries, and outer space is the perfect place to showcase one’s high-tech capabilities.

Under President Xi Jinping’s rule, China's "space dream", as he calls it, has been put into overdrive. In short, China plans to fully assemble its own space station by the end of 2022, to build a base on the moon and have manned missions to Mars in its attempt to become a world-leading space power mastering independent innovation in the space industry. China’s massive investments in space technology and its activities in space embody the pinnacle of technological achievement.

A Panda astronaut as Olympic mascot

While the International Olympic Committee for decades has preached that sport and politics should not mix, China has historically been quite extraordinary in its use of sport for political purposes, and the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics is a perfect platform to showcase the host nation’s space ambitions to the outside world and its own population. A key role will be played by the mascot for the Beijing 2022 Games, the panda astronaut called Bing Dwen Dwen.

The official mascot for a major international sporting event such as the Olympics and the World Cup may have a greater significance than first assumed. The Olympic mascot from the 1980 Moscow Olympics will forever be imprinted in the memory of the Soviet and Russian people. The brown bear, Misha, became a strong symbol of the 1980 Olympics, and the famous tear that Misha shed at the closing ceremony was reproduced by Putin's polar bear mascot at his until then biggest prestige project: The 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi.

According to political scientist Joseph S. Nye, power is the ability to influence the behaviour of others to get the outcomes one wants. This can be achieved by either ‘hard power’, which is based on the use of military or economic power, or ‘soft power’, which is based on attraction rather than coercion. In the article ‘Soft power, ideology and symbolic manipulation in Summer Olympic Games opening ceremonies: a semiotic analysis’, Chris Arning describes how mascots can function as soft power producing properties, as they are often designed to demonstrate both a soft heart and confidence and strength to be able to let "the mask of power slip".

The mascots’ capability to produce soft power lies in their ability to be "whimsy", which can be defined as a "playful creation" that can evoke a feeling of the unexpected and that has a seductive charm. With a playful whim and an instant surprise, the mascots can seduce the audience and the viewers out of their awe and into a state of joy, which is part of the symbolic manipulation.

With Bing Dwen Dwen, China will bring back the panda as an Olympic mascot. China’s extremely popular animal ambassador was also one of the five mascots of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, and it was also the symbol of the Asian Games in Beijing in 1990.

The official video introduction of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Mascot, Bing Dwen Dwen.

Pandas have for decades been a unique part of China’s public diplomacy, the so-called panda diplomacy, but in the case of the 2022 Olympic Games, there is also an underlying political message associated with the panda and its name Bing Dwen Dwen. "Bing" means ice and according to the official description it also symbolises purity and strength, and "Dwen Dwen" represents children. The mascot "embodies the strength and willpower of athletes and will help to promote the Olympic spirit", the description says.

But Bing Dwen Dwen is also portrayed as an astronaut and in the official introduction video, the mascot arrives on earth from space before he returns into outer space where he high-fives an astronaut hanging in space attached to Tianzhou 1.

The Olympics to the moon

In December 2020 Olympic flags, emblem pins, and mascot toys returned to earth after a trip to the moon onboard China’s Chang’e-5 probe. Chang’e-5 is the fifth lunar mission of the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program, and on December 17 the return capsule of the Chang’e-5 probe touched down on Earth after a 23-day space journey, bringing back not only China’s first moon samples but also the iconic Beijing 2022 items. The items were carefully handed over to the Beijing 2022 Organizing Committee in a televised tv-show.

It is not the first time that China has had a mission to the moon. In January 2019, China became the first country in history to land a probe on the moons ‘dark side’. But China’s ambitions go way beyond that and has its eyes set on Mars. And they are already there. In May 2021, China’s Mars probe Tianwen-1 successfully completed a historic landing on the surface of the red planet, leaving a Chinese footprint on Mars for the first time. And what better way to highlight these achievements than at the 2022 Winter Olympics opening ceremony where billions will be watching?