A European model of sports financing: under threat?

Households were used to be the major source of sport finance in Europe, and then came local authorities, enterprises and the (state) government. Such was the last state of knowledge about the shape of a European model of sport financing. The only problem is that this knowledge dates back to 1990 when a study (Andreff et al., 1995)1 had been achieved on a sample of twelve European countries; but it had not been updated so far, except in some countries like France and Germany. Thus, it was urgently needed to update it. The question here is one of financing overall physical and sporting activities – corresponding to what is defined as accounting for national sport expenditure – in sampled countries, and not only professional sports finance whose structure has deeply transformed in the past two decades as exhibited in Andreff & Staudohar (2000).

In 2005, the European model of sport financing has kept the same shape as in 1990 according to a most recent study achieved by those who are co-authoring this article (Amnyos, 2008), in response to a call of the French Ministry for Health, Youth, Sports and Associative Life and the French State Secretary for Sports. Beyond providing updated empirical evidence as regards to sport financing structures, the aforementioned study points at a number of risks and threats hanging over the European model of sports. In the following, we present these threats after a synthetic view of major results derived from an inquiry based on a questionnaire filled by European ministries for sports for the reference year 2005. The country sample encompasses all the 27 European Union member states, including Bulgaria and Romania, even though they acceded to EU only as of 1st January 2007.

Shaping a European model of sports financingSports financing is meant to cover all the sources of funds flowing into sport. On the one hand, there are sources of public finance: the (state) government, in particular the ministry in charge of sports, but also other ministries such as the Ministry of Education, the Ministry for Defence, and local authorities at a regional (regions, provinces, districts, Länder) and local (municipalities, counties, agglomerations) levels. On the other hand, privately-owned money is injected into sport by enterprises (sponsorship, television broadcasting rights) and households (purchases of sporting goods and services such as participation fees, ticketing and so on). Once calculated, the average structure of sport financing2 over 13 countries3, exhibits that households expenditures account for nearly one half of overall sports finance. Local authorities have a 24% share of overall sports finance, enterprises 14% and governments 12%. These data pertain to direct financing of national sporting expenditures.

An indirect source of sport finance, through alleviated expenditures, consists in tax holidays. Reduced taxation rates are offered to those individuals and enterprises which bring funds into sport. On the other hand, those sport organisations which supply public utility sporting activities usually benefit from alleviated VAT (value added tax) rates or reduced social contributions paid on wages. Overall, 21 EU countries mobilise one or the other partial tax exemption.

Last not least, voluntary work is a non financial resource supply to sport without which the latter could not function properly. If volunteers did not exist, those tasks and functions they accomplish should be fulfilled by waged workers. In an indirect way, voluntary work avoids sport decision makers to attract even more monetary finance. However, it is not easy to measure in monetary terms how much is brought into sport by volunteers’ non remunerated work. In the above mentioned study, we have proceeded with estimating two monetary values of voluntary work, one taking into consideration domestic average wage and the other one half average wages. In those 14 EU countries where available data enable calculation, monetary value of voluntary work is bigger than all sport public financing.

A significant share in GDPCalculated per inhabitant, sport financing is very much scattered across European countries, from 8 euros per capita in Bulgaria up to 500 euros in the Netherlands. Compared to 1990 (Andreff et al., 1995), average amount of sport finance per inhabitant has sharply increased in constant euro: in the six countries which are common to the 1990 and 2005 samples4, average increase in sport financing is 37%, with a maximum increase in France and the United Kingdom (respectively +63% and +61%). The ratio between overall sport financing and GDP has risen on average from 1990 to 2005, though to a smaller extent (+24%). Albeit the two country samples are different, the share of sport financing in GDP was in the range of 0.26% in Denmark to 1.61% in Portugal in 1990 and from 0.21% of GDP in Bulgaria up to 1.76% in France in 2005. Increased variance is primarily due to the accession of Central and Eastern European countries to the EU.

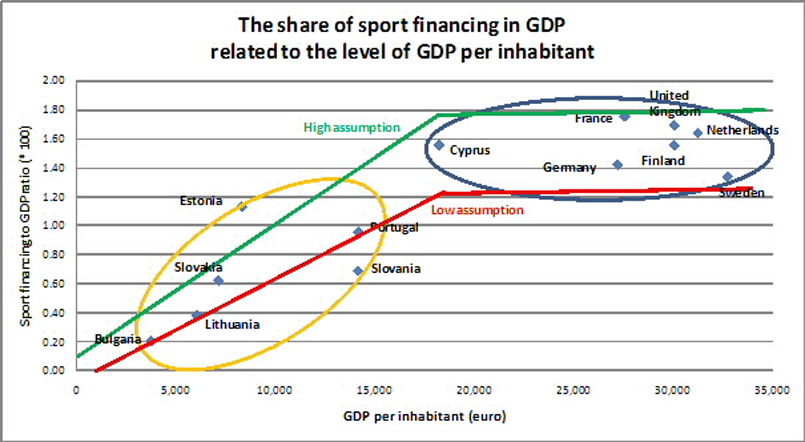

The share of sport financing in GDP is correlated to the level of GDP per inhabitant: the richer a country, the more significant is the share of its GDP devoted to sport finance. It is so in particular with regards to private financing. The following graph shows where the 13 countries which provided data are standing in this respect.

From the graph a threshold shows up in the relationship between GDP per inhabitant and sport financing to GDP ratio at about €18,000 GDP per capita. We have estimated, on the basis of this relationship, overall amounts of sport financing in those 14 countries that have not been able to provide all requested data, under the two following assumptions:

- Regarding countries with a GDP below €18,000 per inhabitant, the ratio is assumed to be exactly proportional to the level of GDP per capita, just like in the relationship that is observed on the left-hand side of the graph (low assumption).

- As to countries with a GDP per inhabitant higher than €18,000, the ratio is assumed to be practically constant, as in the right-hand side of the graph (high assumption).

| Countries with GDP lower than €18,000 per inhabitant | Countries with GDP higher than €18,000 per inhabitant | |

|---|---|---|

| High assumption | Coefficient : 8*10-5 | 1.7 |

| Low assumption | Coefficient : 6*10-5 | 1.4 |

These two assumptions have enabled us to complete those amounts of sport financing missing in our data set and estimate overall amount of sport finance in all 27 EU countries altogether to about €160-170 billion, i.e. nearly 1.5% of EU GDP.Regarding the structure of sport finance, two major features are to be stressed:

- The share of public financing reaches from 8% (United Kingdom) up to 78% (Bulgaria) of overall sports finance. Public share diminishes when the level of GDP per capita increases.

- Sport financing by local and territorial authorities is practically non-existing in some countries (Malta, Bulgaria); a maximum is witnessed in Germany where financing by local authorities makes up for 96% of all public sports finance.

Ambiguous government financing of sportsAll ministries in charge of sports in the 27 EU countries show €2.9 billion as the cumulative value of their budgets, that is 6 euros per inhabitant on average. One witnesses a sort of ambiguity in the sport financing strategy of most EU member states. There is a marked discrepancy, not to say a contradiction, between actual orientation of sport financing and advertised promotion of sport values. One side of the coin is that governments do push forward health and social objectives of sport, the latter being displayed as a well being and social integration factor, which is at odds with financing priorities. Indeed, the other side of the coin exhibits a government tendency to gear significant financing from the sports ministry toward elite sport (via sport federations targeting high level sport or via prioritising specific disciplines) and organising mega sport events.Such ambiguity could be resolved by assuming a snow ball effect as follows: the government finances high level sport with the background idea that best sportsmen and women victories and their media exposure will act as an incentive to all population, namely the youth, to get involved into sport practice. However, there are two important prerequisites for such an assumed effect to be valid: . In such a vision of sport, all sport participating bodies must be associated together in decision making, first of all major non governmental financiers supporting sport clubs and infrastructures (that is local authorities and enterprises), in order to ensure welcoming and training new sport participants. . A peculiar attention must be drawn at access to sport participation; otherwise most poor people would have no way to accede. Both prerequisites are far from being fulfilled in a number of EU countries and, consequently, government financing targeted to high level sport cannot, by itself, initiate or maintain a virtuous circle of sport participation. Threats over the European sports modelLet us briefly remind in what does consist the European sports model. Its first specific characteristic is a pyramidal structure with mass sport participation at its foundations and high level sport practice at its summit. A second specificity is that sport contests are ruled through a promotion-relegation system between higher and lower leagues (divisions) organised by national sport federations. A third feature is that all sport is structured around national federations and local clubs. The fourth one is voluntary work which is a pillar of a well functioning sport system.

Sport financing is primarily allocated to following functions: subsidies to sport federations and clubs, sport infrastructures, sport events, and waged jobs in the sport sector. Distinguishing three categories of sport participation, i.e. amateur sport contests, leisure and health sport practice, and high level sport, an analysis of sport finance allocation in Europe (Amnyos, 2008) shows that each source of finance tends to be geared towards one category of sport participation rather than the other two. Household expenditures are oriented in priority toward leisure and health sport practice and then to high level sport, through attending sport events. Enterprises are used to privilege high level sport with high media exposure in a limited number of sport disciplines. Local and territorial authorities first allocate their sport budgets to amateur sport contests. Government concentrates its financial allocation on to high level sport.

Sport financing is primarily allocated to following functions: subsidies to sport federations and clubs, sport infrastructures, sport events, and waged jobs in the sport sector. Distinguishing three categories of sport participation, i.e. amateur sport contests, leisure and health sport practice, and high level sport, an analysis of sport finance allocation in Europe (Amnyos, 2008) shows that each source of finance tends to be geared towards one category of sport participation rather than the other two. Household expenditures are oriented in priority toward leisure and health sport practice and then to high level sport, through attending sport events. Enterprises are used to privilege high level sport with high media exposure in a limited number of sport disciplines. Local and territorial authorities first allocate their sport budgets to amateur sport contests. Government concentrates its financial allocation on to high level sport.

All three categories of sport participation are unevenly under threat today as regards to their financing. One witnesses that a tendency for private finance to flow into media-exposed sports is reinforced by a majority of European governments giving priority to high level sport which, together, threat the pyramidal structure to be destroyed. The pyramid foundations are jeopardised by financing shortages and a slower momentum in voluntary work development while the summit tends to break up from the foundations. Deepening disparities between sport disciplines even affect high level sports. Moreover, when looking at high level sport, convergence across EU member states is merely confined to competing in international sport contests and hosting and organising mega sport events. Finally, there is a risk that current systems of betting and gambling revenue paybacks to public extra-budgetary funds for sport will be challenged and this is a major concern for all EU governments. Both risk and concern have their roots in a rapid growth of sport betting and gambling on line the amount of which is uneasy to detect and, therefore, to tax.Toward common financing guidelinesIn the face of aforementioned threats and risks, the shape of the European model of sport financing as well as its different national variants5 are at stake. Securing further sport financing probably requires an update of the European model along some common guidelines.In the European vision of sport organisation6, the cornerstone must remain solidarity between different sports: a majority of EU member states are running various solidarity mechanisms within the sport sector. The most widespread solution is vertical solidarity: in a same sport discipline, there is some redistribution scheme from those sport practices that attract private financing (namely TV rights revenues) to mass sport participants. Horizontal solidarity between different sport disciplines is also found in some countries (for example within general sports clubs like Steaua Bucharest in Romania). Solidarity can even be both vertical – from high media revenue professional football to amateur football – and horizontal when professional football revenues are redistributed to all different sports, like the Buffet tax on professional football in France. However, in most EU countries, solidarity mechanisms redistribute too few monies to sustain mass sport practice. The financial godsend resulting from betting and gambling revenue paybacks to sport is increasingly challenged by EU competition policy and, by the same token, public monopolies in charge of managing betting and gambling activities are under threat of being dismantled. It is the most destabilising factor of sport financing that is identified by ministers for sports. In fact, revenues redistributed from betting and gambling can make up to three quarters of a sports minister’s budget (like in Greece) and one quarter of overall public sport financing. It is basic that such source of finance will still contribute to sport development in Europe.The issue of sport governance in Europe derives from the need for stabilising and securing sport finance. Thus, local authorities must find their due place in sport public policy making including with a real participation to the definition of sport social and economic objectives and priorities, as well as resource mobilisation, together with (state) central governmentAnother common guideline to update the European sport model could consist in favouring private financing by individuals and enterprises in view of developing mass sport. Here again, sport governance matters and it should be analysed further and designed in such a way as to avoid a takeover of sport by purely financial interests. The task is to be undertaken at both levels of sport federations and clubs – in order to supply sport services that fit with demand – and government in view of creating investment attractiveness into mass sport. With a more secured finance the sport sector could afford stabilised and professionalized jobs in the long run. As to voluntary work, it is acknowledged by all sport participants as a pillar of European sport, but it is urgently needed to support it so that it could reproduce itself at the required speed in appropriate magnitude. Stimulating tools could consist in more recognition and more social positive evaluation of volunteers’ functions as well as incentives provided to some targeted parts of the population (migrant workers, women, and youth) to get them more involved in voluntary work. In order to dispose of a statistical follow up regarding how various sources of sport finance are evolving and drawing from this all implications for European sport organisation, a more regular measurement tool (than one study every fifteenth year) is to be implemented. Besides a satellite accounting of sport that is elaborated on at the EU level, but which is complex to build up, a recurrent update of a study similar to the present one could provide very much useful current data.

All three categories of sport participation are unevenly under threat today as regards to their financing. One witnesses that a tendency for private finance to flow into media-exposed sports is reinforced by a majority of European governments giving priority to high level sport which, together, threat the pyramidal structure to be destroyed. The pyramid foundations are jeopardised by financing shortages and a slower momentum in voluntary work development while the summit tends to break up from the foundations. Deepening disparities between sport disciplines even affect high level sports. Moreover, when looking at high level sport, convergence across EU member states is merely confined to competing in international sport contests and hosting and organising mega sport events. Finally, there is a risk that current systems of betting and gambling revenue paybacks to public extra-budgetary funds for sport will be challenged and this is a major concern for all EU governments. Both risk and concern have their roots in a rapid growth of sport betting and gambling on line the amount of which is uneasy to detect and, therefore, to tax.Toward common financing guidelinesIn the face of aforementioned threats and risks, the shape of the European model of sport financing as well as its different national variants5 are at stake. Securing further sport financing probably requires an update of the European model along some common guidelines.In the European vision of sport organisation6, the cornerstone must remain solidarity between different sports: a majority of EU member states are running various solidarity mechanisms within the sport sector. The most widespread solution is vertical solidarity: in a same sport discipline, there is some redistribution scheme from those sport practices that attract private financing (namely TV rights revenues) to mass sport participants. Horizontal solidarity between different sport disciplines is also found in some countries (for example within general sports clubs like Steaua Bucharest in Romania). Solidarity can even be both vertical – from high media revenue professional football to amateur football – and horizontal when professional football revenues are redistributed to all different sports, like the Buffet tax on professional football in France. However, in most EU countries, solidarity mechanisms redistribute too few monies to sustain mass sport practice. The financial godsend resulting from betting and gambling revenue paybacks to sport is increasingly challenged by EU competition policy and, by the same token, public monopolies in charge of managing betting and gambling activities are under threat of being dismantled. It is the most destabilising factor of sport financing that is identified by ministers for sports. In fact, revenues redistributed from betting and gambling can make up to three quarters of a sports minister’s budget (like in Greece) and one quarter of overall public sport financing. It is basic that such source of finance will still contribute to sport development in Europe.The issue of sport governance in Europe derives from the need for stabilising and securing sport finance. Thus, local authorities must find their due place in sport public policy making including with a real participation to the definition of sport social and economic objectives and priorities, as well as resource mobilisation, together with (state) central governmentAnother common guideline to update the European sport model could consist in favouring private financing by individuals and enterprises in view of developing mass sport. Here again, sport governance matters and it should be analysed further and designed in such a way as to avoid a takeover of sport by purely financial interests. The task is to be undertaken at both levels of sport federations and clubs – in order to supply sport services that fit with demand – and government in view of creating investment attractiveness into mass sport. With a more secured finance the sport sector could afford stabilised and professionalized jobs in the long run. As to voluntary work, it is acknowledged by all sport participants as a pillar of European sport, but it is urgently needed to support it so that it could reproduce itself at the required speed in appropriate magnitude. Stimulating tools could consist in more recognition and more social positive evaluation of volunteers’ functions as well as incentives provided to some targeted parts of the population (migrant workers, women, and youth) to get them more involved in voluntary work. In order to dispose of a statistical follow up regarding how various sources of sport finance are evolving and drawing from this all implications for European sport organisation, a more regular measurement tool (than one study every fifteenth year) is to be implemented. Besides a satellite accounting of sport that is elaborated on at the EU level, but which is complex to build up, a recurrent update of a study similar to the present one could provide very much useful current data.

End notes:

- W. Andreff, J.-F. Bourg, B. Halba, J.-F. Nys, Les enjeux économiques du sport en Europe: financement et impact économique, Dalloz, Paris 1995 (this reference is the published version of a study achieved for the Council of Europe).

- It is calculated as a non weighted (by country) mean, thus it is in fact a mean of financing structures observed in responding countries.

- Only 13 out of 27 countries have been able to provide data about all the four public and private sources of sport finance.

- Finland, France, Germany, Portugal, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

- Which are not dealt with in this article, see Amnyos (2008).

- The European sport organisation is distinct from the North American one, from the former Soviet state-run sport system and from a sport less endowed with resources in developing countries (Andreff, 2001).

References:

- Amnyos, Etude du financement public et privé du sport, Etude réalisée dans le cadre de la présidence française de l’Union européenne, Ministère de la Santé, de la Jeunesse, des Sports et de la Vie Associative et du Secrétariat d’Etat aux Sports, Paris, octobre 2008.

- Andreff W., The Correlation between Economic Underdevelopment and Sport, European Sport Management Quarterly, 1 (4), 2001, 251-79.

- Andreff W., J.-F. Bourg, B. Halba & J.-F. Nys, Les enjeux économiques du sport en Europe: financement et impact économique, Dalloz, Paris 1995 (version publiée d’une étude réalisée pour le Conseil de l’Europe).

- Andreff W. & P. Staudohar, The Evolving European Model of Professional Sports Finance, Journal of Sports Economics, 1 (3), 2000, 257-76.